(this article was originally published in We Love 2019, download the full magazine HERE)

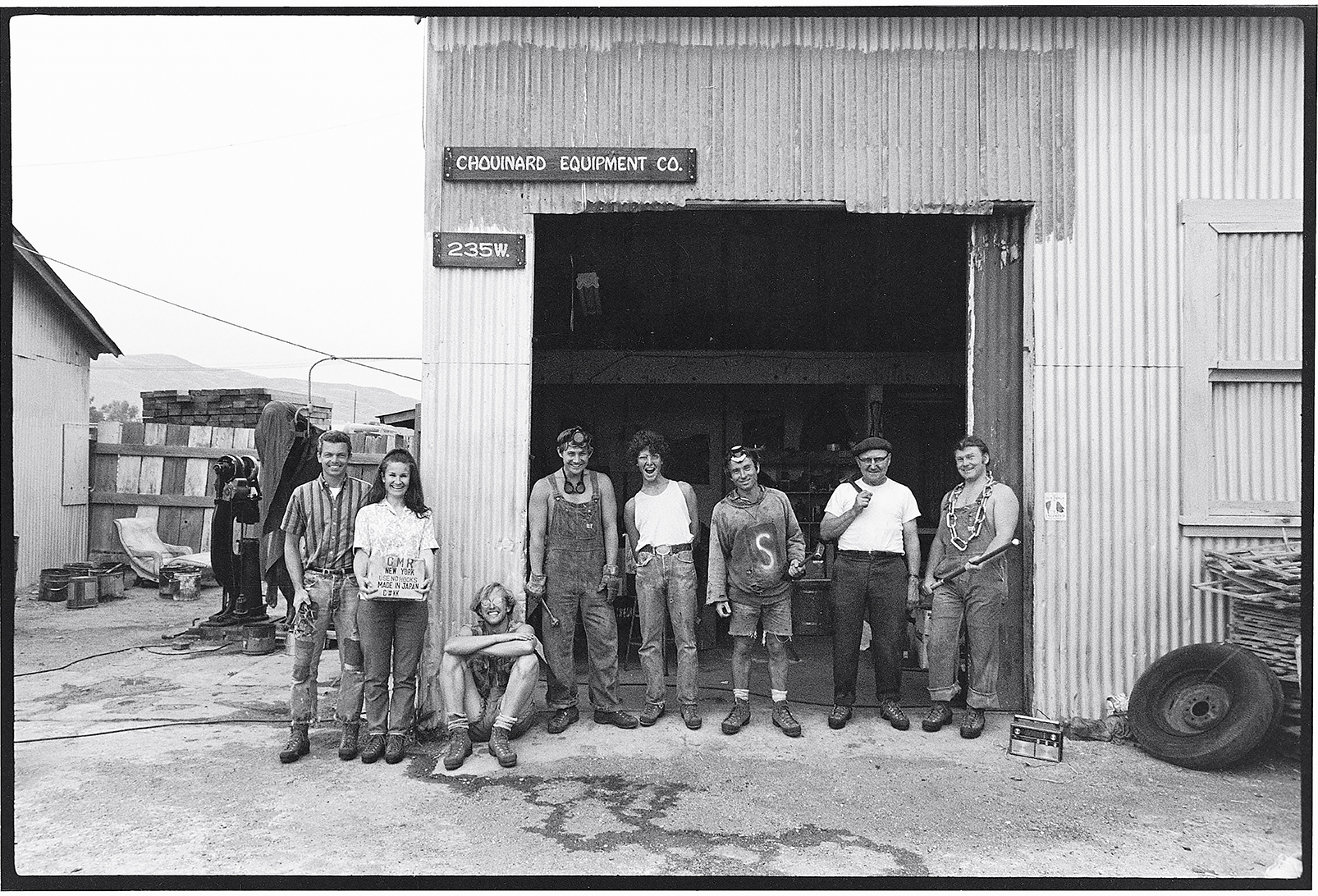

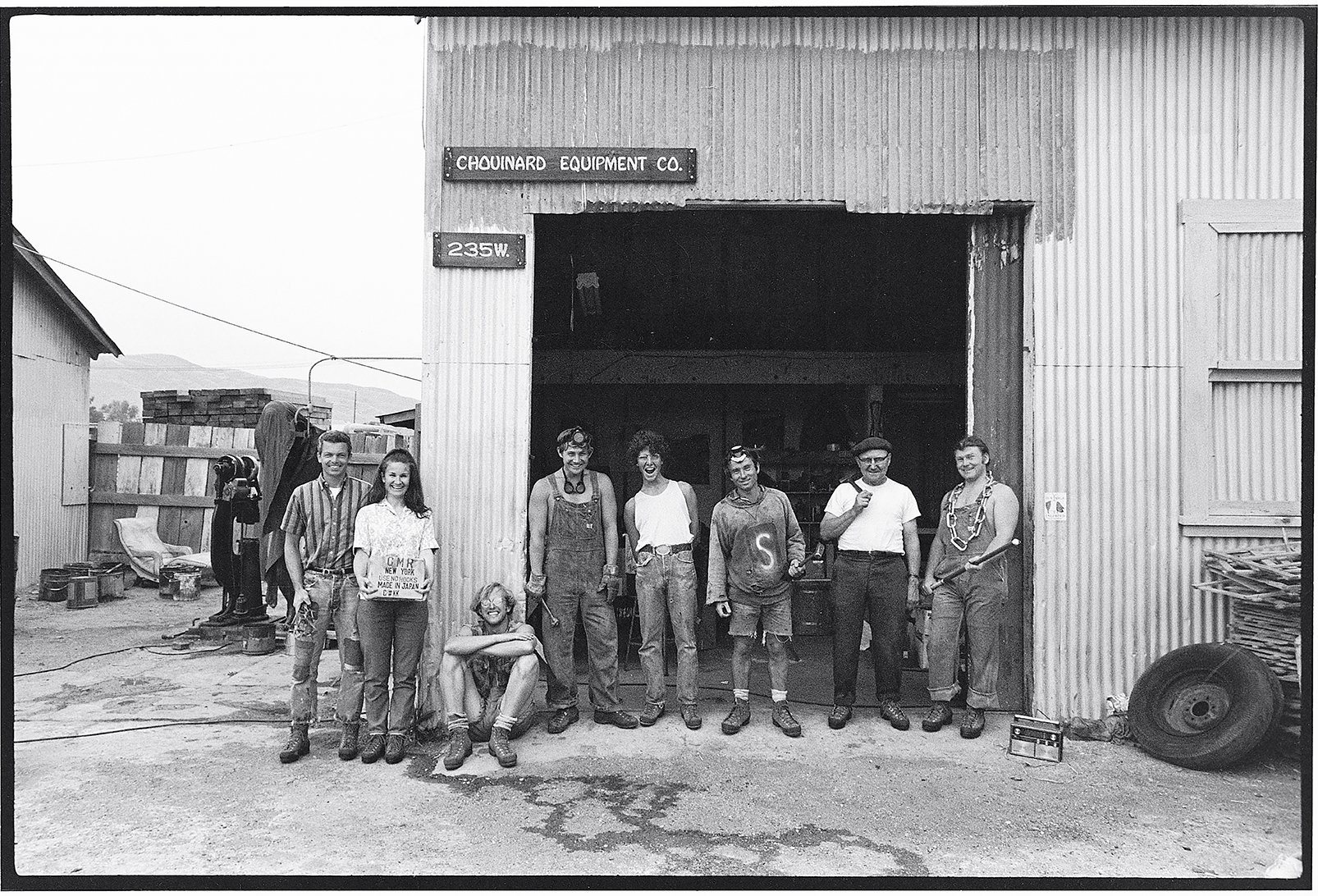

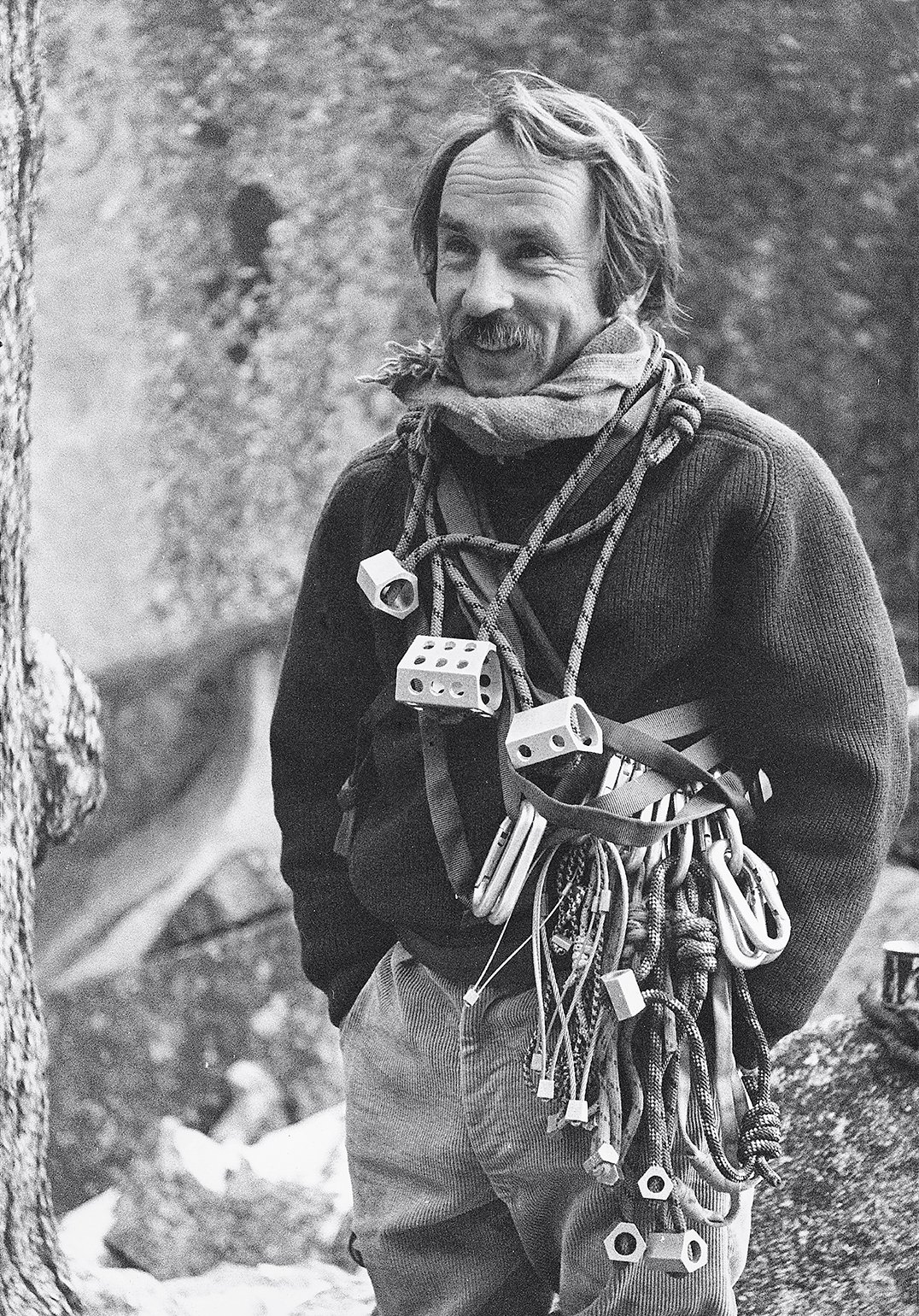

When Patagonia’s founder Yvon Chouinard started making climbing equipment for himself and his friends in the 1960s, it was always with a great respect for the natural environment in mind. Forty-five years later, the company’s collection has grown to incorporate clothing and equipment for skiing, snowboarding, surfing, fly fishing, paddling and trail running. And as Patagonia has grown, so too has its interest in preserving the nature in which these sports take place.

“We have always had an appreciation of the wild places around the world and a concern for their protection,” says Ryan Gellert, the company’s general manager for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “This has steadily evolved as the issues that our planet faces have grown in significance.”

Ryan Gellert, Patagonia's general manager for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Photographed by Annica Eklund.

Ryan Gellert, Patagonia's general manager for Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Photographed by Annica Eklund.

And grow they have: since the industrial revolution, the impact of humans on the environment has led to a depletion of natural resources, pollution of air and water, and destruction of rainforests and biodiversity. A report in October by the UN warned that we only have until 2020 to find a way to keep the global temperature from rising more than a critical maximum of 1.5°C, above which we are likely to see more natural disasters and dangerously unpredictable weather. If the UN target is to be met, the impact of industry on the planet is one of the major factors that needs to be addressed.

Increased awareness around environmental degradation means businesses of all kinds can no longer afford to ignore these issues – especially those engaged in industries such as clothing production, which uses huge amounts of natural resources (it takes around 20,000 litres of water to produce 1kg of cotton) and produces pollution in the form of dyes and pesticides. For Patagonia, the problem is all the more complex because its customers, as lovers of the great outdoors, are perhaps more attuned than average to environmental issues.

Moreover, its entire business relies on society being able to continue to enjoy nature in its best form. Whether for the sake of the environment, its bottom line or both, Patagonia has embedded sustainability deep into its design, marketing and business strategies. The company’s mission statement now pledges to “cause no unnecessary harm” and “use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis”.

In design terms this has meant experimenting with materials, manufacturing techniques and the supply chain. For example, it took years of research to find nylon products that could be recycled to create fabric of high quality. Patagonia ultimately settled on a combination of post-industrial waste, yarn from a spinning factory, waste weaving mills and discarded industrial fishing nets.

It has also introduced high-performance materials such as Synchilla, a soft, double-faced fabric that does not suffer from surface degradation; Capilene, a new polyester with a high melting temperature suitable for commercial dryers; and Yulex, a natural rubber that is used to produce wetsuits.

Patagonia also claims to be the first outdoor clothing manufacturer to make fleece out of recycled plastic soda bottles, while other ranges are made of down reclaimed from old cushions and bedding, and wood pulp that is extruded through fine holes to produce fibre. Since 1996 it has used 100 per cent organic cotton, instead of the pesticide-intensive variety, and it has introduced hemp into its product line in the hope that laws surrounding the production of this durable and eco-friendly material will be loosened in future.

These measures, and others like them, have allowed Patagonia to continue to operate as a global business while still maintaining an anti-big business ethos, appealing to people who consider themselves to be environmental activists but still want branded products. As Chouinard wrote in his book Let My People Go Surfing:

“I’ve never respected the profession. It’s business that has to take the majority of the blame for being the enemy of nature.”

What these innovations do not solve, however, is a crucial question: how can a business engaged in mass manufacturing and global distribution reconcile its existence with society’s inherent need to produce and transport less? This conflict is one that design businesses have become increasingly conscious of in recent years. The annual churn of new designs at fashion and furniture weeks is emblematic of the wider societal problem of a culture where items of low quality – whether $10 jeans, a mobile phone or a flatpack shelving unit – are produced cheaply in poor countries, with consumers then encouraged to replace products rather than investing in longevity or repairing them.

Today’s heightened climate of environmental awareness is not, however, the first time that such questions have arisen in Patagonia’s history. Before launching his clothing range, Chouinard started out making reusable steel pitons for climbing, rather than the commonly used soft iron ones that would be left in the rockface. By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest climbing hardware supplier in the US, but its success was a double-edged sword: as climbing became more popular, the impact on well-used routes was visible. Pitons, which had to be hammered into rock, were causing damage to the very environments that inspired Chouinard to take up the sport. For the entrepreneur, this was an early encounter with the conflict at the heart of his business – that in seeking to help people enjoy nature, he was also helping to destroy it.

In response, Chouinard and his partner Tom Frost made the decision in 1972 to phase out their lucrative production of pitons, and start making aluminium chocks that could be wedged in by hand. “Mountains are finite, and despite their massive appearance, they are fragile,” the duo wrote at the time.

Photography by Patagonia.

Photography by Patagonia.

Photography by Patagonia.

Photography by Patagonia.

Chouinard and Frost advocated for what became known as ”clean climbing”. From an economic standpoint, it was a risk to be guided by environmental concerns rather than sales figures – but one that paid off.

Within months, sales of chocks rocketed. Just over a decade later, Patagonia has reached beyond the hardcore sporting community to become a mainstream fashion brand – according to Forbes, its revenue rose from $20m to $100m between the mid 1980s and 1990. Then the 1991 recession hit and the company was forced to cut 20 per cent of its workforce to help pay its debts. For many companies, this would have been a moment to refocus on the bottom line, but Patagonia took a different approach and put sustainability at its heart. In the 1980s the company had already spent money and time supporting initiatives focused around clean water, air and soil. In 2002, it formalised this idea by co-founding 1% for the Planet, which gives away 1 per cent of all sales to grassroots environmental groups worldwide. Since 1985, the company has given nearly $90m in grants and donations to such initiatives. Its 1991 catalogue pointed to an unavoidable conclusion that, in order to live up to its sustainable values, it needed to discourage its own customers from buying too much.

In 2011, Patagonia ran an advert on Black Friday that said “Don’t Buy This Jacket”, explaining the environmental impact of that particular item of clothing. It is also calling on customers to keep each item for an extra nine months. In 2013, it launched Worn Wear, a scheme that allows customers to trade in their used Patagonia clothing in exchange for store credit, which then gets repaired and resold. As a business, it is banking its future on a more sustainable mode of consumption.

Of course, such a strategy only works if you’re confident that your product is the one people will choose, and if it’s reliable and durable enough to last. It’s another risk, but one it seems that Patagonia is willing to take.